In the midst of the current debate about whether we should be getting kids back to school as quickly as possible, or taking it slowly slowly, this article came out in The Conversation, referencing a number of medical journal articles, documents from various government websites (typically Health Department publications), and articles from other news media publications in Australia. As a high school teacher with medically vulnerable people in my family, I am naturally skeptical of any call to rush us back to school because, frankly, I don’t want members of my family to contract this virus from me. I also quite like my students, and so I think it’s important to be reasonably certain that no harm will occur by encouraging students to return to school too soon. So I take a fairly careful look at any evidence that claims schools are safe. I should add, I’m reasonably ok with the argument that when kids tend to contract COVID19, they tend to have mild symptoms, or remain asymptomatic, and also that they tend to spread it less than adults (a natural consequence of mild symptoms), although I wouldn’t say the evidence on this is yet proven beyond reasonable doubt. I also think there are broader issues to consider.

To the article – via Twitter, I was challenged to read through the sources of this article and provide a critique. Which is how we ended up here. To be clear, I am not critiquing the scientific articles that are referenced in The Conversation article. I don’t have the qualifications or experience for that. However, I do feel quite up to the challenge of critiquing the claims made in The Conversation based on the medical sources. That is, have the journal articles been fairly represented, or are there qualifications to the conclusions made by the authors in The Conversation based on limitations of the data or conclusions in the sources. Or are the statement in The Conversation simply unsupported in the sources.

There should be nothing controversial about doing this. We teach high school students to evaluate these sorts of claims as part of their regular study in senior sciences and humanities. This is also a regular part of the discourse in scientific literature. If you disagree with my conclusions, I’m open to having a conversation around that, and correcting the record if I believe it’s justified.

Methodology: So, my methodology in this is to identify the claims made in The Conversation, and evaluate those claims against the sources the authors have provided, taking in to account limitations of the studies, and other information that may be relevant to those sources. I’m going to assume that the sources used are in themselves reliable (which I’m sure the authors of the article in The Conversation won’t quibble with) within the boundaries of the limitations identified in the sources themselves, and the context of the data. I won’t evaluate claims made based on media articles, because the methodology just isn’t there to assume that the claims in the media sources are reliable in the first place without going to their own sources, which aren’t always identified. I won’t seek to discredit the claims by referencing other sources that come to a different conclusion – I only want to investigate the basis of the claims made by the authors in determining whether their statements stack up or not. And I will do this in the order of claims and sources in the article itself. So, starting at point 1.

1. Kids get infected with coronavirus at much lower rates than adults

The first scientific source the authors refer to is this article. The title of the article is ‘Epidemiology of COVID-19 Among Children in China’ and is published in a reliable American Pediatrics journal. It investigates the characteristics of of COVID19 in pediatric patients, mostly in Hubei Province, and concludes that children of all ages are susceptible to COVID19. At no point does it compare the rate of infection with adults. The methodology used in this report indicates that it only investigated children that were symptomatic, some of whom were confirmed to have been infected with the 2019-nCoV virus, and some of whom were assumed to be infected due to their symptoms.

The dates during which the data was gathered was from the 16th January to the 8th February. Chinese New Year occurred on the weekend of the 25th January, and the lockdown in Hubei began on the 23rd of January. So for most of the period of data collection, children were not at school, although some would have contracted the virus during the period before the lockdown when schools were open. However, this makes it difficult to draw conclusions on the safety of school, and transmissions at school, from this report.

A second source, claiming less than 150 children below 15 years have been infected opens a link to an index page on the Australian Department of Health website, and nothing on that page can support that claim. It seems likely to be true. I will note here that half of students in high school will be 15 years and older (including all the students I teach), something unfortunately not identified in The Conversation article as important.

A third source, also from the Australian Department of Health website does tend to support the idea that a small proportion of identified cases of COVID-19 in Australia are children, however, I think it is worth remembering the limitations of the data here in that for a significant period of time, testing was limited to people who had been overseas, or in close contact with people overseas AND were showing specific symptoms. Children tend to be under-represented in our travelling population, and it is accepted that children also tend to be more likely to be asymptomatic or have mild cases, so it should be no surprise that there are less identified cases in children. The sort of data that would make this point more supportable would be data on testing by age, and the proportion of people testing positive in each age group. The data may be out there, but it is not provided here.

None of the sources provided in this section of the article reliably support the idea that kids get infected with corona virus at a lower rate than adults.

2. Children rarely get severely ill from COVID-19

Going by the references provided, this is well supported, and backed up in other studies. There certainly are cases of children and infants becoming ill and dying, often linked to a range pre-existing conditions, but these are rare. I think this last point is important because parents of children with pre-existing conditions need to be aware of this, and not simply told their child will be safe at school.

So there are a couple of caveats to this claim, and that is that children rarely become acutely ill form COVID-19. We have no idea about the long term impacts this virus on children or adults, simply because it is so new.

So I think the claim could be better stated as Healthy children rarely become acutely ill from COVID-19. Other children may be at higher risk.

It is worth noting this statement in The Conversation Article from this section: “A study in Iceland showed children without symptoms were not detected to have COVID-19. No child below ten years of age without symptoms was found to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 in this study.”

It is referencing the linked journal article, which states: “Children under 10 years of age were less likely to receive a positive result than were persons 10 years of age or older, with percentages of 6.7% and 13.7%, respectively, for targeted testing; in the population screening, no child under 10 years of age had a positive result, as compared with 0.8% of those 10 years of age or older.”

I believe the statement above in The Conversation is trying to extrapolate beyond the scope of the report it references. Yes, it adds the phrase ‘in this study’, but given the number of other studies showing asymptomatic infection is quite common, the statement should have been further qualified to be reliable as it seems out of kilter with what else we know about this virus and kids.

3. Children don’t spread COVID-19 disease like adults

The first source includes the statement: ‘In these studies the index case of each cluster defined as the individual in the household cluster who first developed symptoms.’ If children do have either mild symptoms (as The Conversation authors claim earlier in their piece), or are commonly asymptomatic, as is widely believed, then it would be hard to identify the children in a household as the index case. The data is compared to other zoonotic viruses where there is clear evidence that children can be index cases for a household, so there may be some validity to this claim. At the same time, the sample size of this report is only 31 households, which is relatively small. I would like more data on this before being so confident about making this statement.

The second source, a study from the Netherlands, indicated that one study relied only on testing patients that arrived at a GP clinic, that already showed symptoms. A second study was still ongoing at the time this document was published and only preliminary results were published. This information would have been a good qualifier for this statement.

I think there is some data to support this statement, qualified by the fact that the data on this is not yet overwhelming (in fact the second source makes it clear that continued study is necessary and ongoing).

4. School children in Australia with COVID-19 haven’t spread it to others

Australia has been very fortunate to have a relatively small caseload of infections, which equally means very few cases in schools at all. So there is a very small sample on which to base this claim. The statement makes a much stronger case than the data allows. There is no attempt here to reference data from other countries where there are many more cases. If data from abroad isn’t relevant in Australia, then perhaps the authors could have explained why.

This sort of statement, which is unsupported except for the absence of evidence, is the sort of statement that is true, until it isn’t. However, there is now at least one cluster in a child care centre in Sydney, with another two centres undergoing contact tracing at the moment. There is also the significant cluster in Marist College, Auckland, in which students have become infected, most likely from staff or other adults. If children do become infected, their parents and families are not going to be less upset or worried because they became infected from their teachers instead of from their friends. Perhaps a better claim to investigate is whether children are becoming infected at schools generally, not whether they infect each other.

So, this statement is mostly true, for Australia, so far, but makes no effort to investigate experiences in other countries, and ignores other paths of infection for students, other than other students.

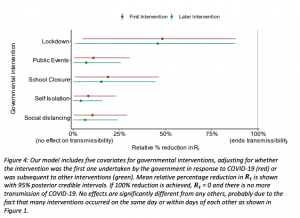

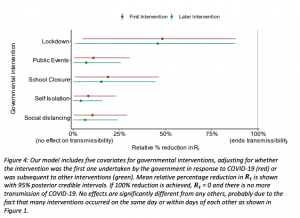

5. There is no evidence closing schools will control transmission

Only one of the three sources referenced in this section refers specifically to data from the current novel corona virus pandemic. I cannot find anywhere in this quite substantial report that makes any statement that supports the claim that there is no evidence that closing schools will control transmission. In fact, it claims that of five key strategies used throughout Europe to control the spread of the pandemic, only Lockdown is more effective than School Closures, and that School Closures is equally effective as the other three key strategies undertaken in Europe of Social Distancing, Self-Isolation and cancelling Public Events. Definitions for these strategies are available in the report from the link at the start of this paragraph.

From the report:

For context, I did hear some reports stating exactly this claim from a study from the University College London, but when the report was analysed in detail, the actual finding was the school closures without other measures would have little impact. So it is the impact of multiple strategies acting together, including school closures, that has resulted in the slowing of the pandemic in Europe.

Summary

When I first read this article, I took it on face value, noting that it was referenced using what appeared to be reasonably reliable sources and journals. It’s only when reading the actual sources that some of the problems with the claims becomes evident.

In any case, the general gist, that schools are safe for students in terms of infection from other students, may be reasonably supported, but with some pretty heavy caveats that our politicians generally fail to make explicit

- Students 15 or over may need to be treated as adults in terms of transmission.

- We don’t yet know if there are long term impacts on the health of children if they contract the virus.

- Adults must practice social distancing as in every other sphere of society. This includes parents (so drop off at the school gate only, no visiting classrooms) and staffrooms, lunchrooms and other places adults congregate.

- Vulnerable people need to isolate (A school near me has 60 teachers classified as vulnerable).

- Students and adults practice good hygiene, with soap and sanitiser readily available

- Schools are thoroughly cleaned throughout the day, particularly high traffic areas

- Activities like sport can’t go ahead.

A lot of those caveats will actually make it very difficult for schools to open for the entire cohort of their student body. In some cases it would make it impossible. Trying to get schools back to normal also ignores the fact that this generates an awful lot of movement around our community, both of children and adults, which in itself increases the risks for infection amongst our school communities.

Frankly, school closures is not just about students. It’s about communities, and needs to be thought of in that context. Is it ideal? No, but we’re not closing school as some sort of grand educational experiment. It’s a once-in-a-hundred-year pandemic. There’s a long way to go still before it’s resolved. Let’s not rush decisions based on incomplete data. Let’s not forget the lesson of thalidomide. It was years before the medical community understood the impact of thalidomide on unborn children. For the children and their parents, the consequences were lifelong. We still have such a limited understanding of the virus. For the sake of the children in our society, we need to slow down, and be certain of the decisions that we make.