Ok, the title is a bit of a mouthful, but I’m hoping that it doesn’t come across as a bit of a jargon-fest.

21st Century Skills

I’m a strong support of the integration of 21st Century Skills into our curriculum, not because they’re particularly techy or trendy, but because they’re really just common sense skills that will help anyone whether it’s the 21st Century, the 22nd, or even the 12th (although it’s a bit late for us to help those people now).

There are a number of documents and programs that attempt to define what the 21st Century Skillset is, and the one I tend to use the most is one developed by Microsoft. I like their work on this because it clearly defines what we can expect to see students doing in class for each of skills, and even describes different levels of use in the classroom, from very basic to advanced (see here for their 21st Century Learning Design rubrics and documents, 21CLD)

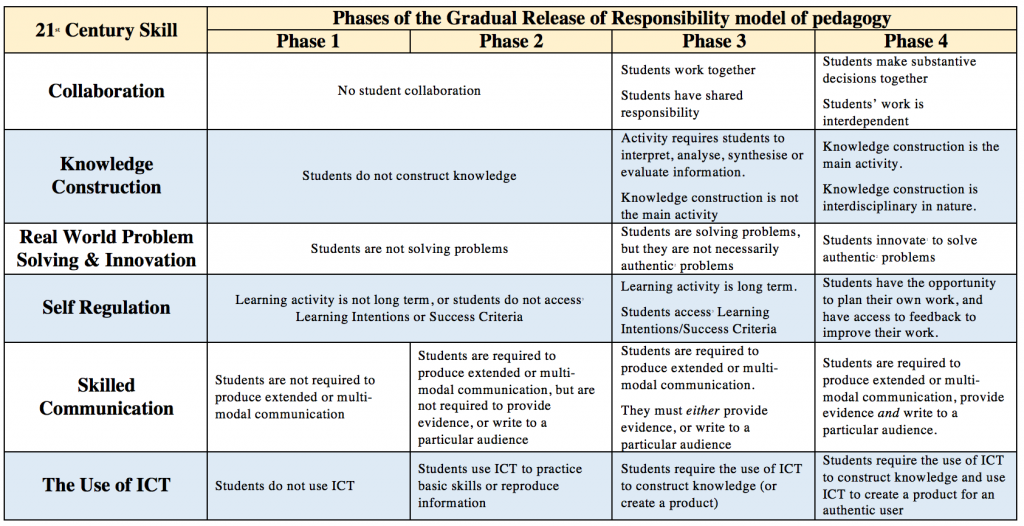

In the 21CLD documents, the 21st Century Skills are listed as Collaboration, Knowledge Construction, Real World Problem Solving and Innovation, Self Regulation, Skilled Communication, and The Use of ICT.

The Gradual Release of Responsibility (GRR) Pedagogical Framework

GRR is a structured pedagogical framework that, as the name suggest, gradually moves the focus of learning from the teacher to the student (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983). It was developed from Zygotsky’s idea of the Zone of Proximal Development (Newman, Griffin, & Cole, 1989). There are four distinct phases in GRR.

- Focussed Lesson: the skill or process to be taught is explicitly modelled by the teacher, with students passively observing.

- Guided Instruction: students attempt the skill or process modelled in the first stage, one step at a time, with teacher support or guidance, rather than modelling.

- Collaborative Learning: students continue to improve their skills at their own pace, but with the support and guidance of their peers rather than the teacher.

- Independent Tasks: students apply their learning in new situations.

The characteristics of learning in the first two phases are best described by the learning theory Behaviourism (Schuh & Barab, 2008). Behaviourism describes learning as direct transmission of knowledge from teacher to student, and as wholly teacher-directed. Behaviourism does not require students to be highly engaged in their own learning, merely compliant with teacher directions. Schlechty (2011) describes this level of engagement as Ritual Compliance, in which students have a low commitment to the work, and display low attention to the task at hand. This is not to say that students cannot display high engagement with a task at these phases of GRR, but it is not necessary that students be highly engaged in order to have success at these phases.

Phase three requires students to be more highly engaged in their work for success. The explicit requirement for collaboration between students in phase 3 requires us to look beyond Behaviourism as an appropriate Learning Theory to other theories. Cosmopolitanism describes learning where knowledge is constructed by the student, collaboratively with peers, from a variety of sources, including but not limited to, the classroom teacher (Schuh & Barab, 2008). That is, learning is not wholly teacher directed, and is not an individual task. Sources of learning could include their own life experiences, peers, experts, or third party sources such as print media or digital sources from the internet. In addition, knowledge is constructed by the student from this broad range of sources. For students to succeed at this phase of GRR, it is a requirement that students at least show a high level of attention to the task, given that they are no longer closely directed, even if they do not care about the task itself (ie have low commitment). Schlechty (2011) describes this level of engagement as being Strategically Compliant, which is characterised as a behaviour where students work hard due to extrinsic motivations, such as a desire to improve grades, or other external rewards. Learning is still teacher-led at this phase, but techniques such as Learning Intentions & Success Criteria (Hattie, 2005, p. 4), and Flipped Classrooms (Abeysekera & Dawson, 2015) work well as it allows students to take ownership of their own rate of learning, and measure their own success against externally-created criteria.

Phase four is the point in learning where we invite students to apply their knowledge and skills in new situations that are authentic and involve real world problem solving. It is in this phase that students have the first real opportunity to choose an application for their new skills that are of personal interest to themselves, with guidance or advice from their teacher. An alternative Learning Theory to Cosmopolitanism that applies to student learning in this phase is Enactivism (Schuh & Barab, 2008), in which students learn collaboratively, and through interaction with the world. For success in this phase, students need to show the full characteristics of Engagement as described by Schlechty (2011), that is, both high commitment and high attention to the task at hand. Students must be intrinsically motivated, and so it is important that the teacher does not arbitrarily assign a task, but involves the students in identifying a task to work towards that is seen to be authentic for the students. PBL (problem based learning, or project based learning) (Buck Institute of Education, n.d.) can be a good a teaching technique that meets these requirements.

Integration of GRR with 21st Century Skills

In an initial attempt to integrate GRR with 21st Century Skills, the table below, shows a mapping between specific activities related to each 21st Century Skill, and the GRR phase in which that activity should be observed.

- In the 21CLD document, innovation is defined as putting students’ ideas or solutions into practice in the real world.

- The authenticity of a product/problem can only be decided by the audience or client, in this case, our students. This reinforces the idea that students must be involved in planning which problems to solve, as they student themselves must see the problem as authentic, not just the teacher.

- Accessing Learning Intentions and Success Criteria is defined as these being both available to students, and actively being used by students. Simply having them available for students is not enough to say they are being accessed by students.

References

Abeysekera, L., & Dawson, P. (2015). Motivation and Cognitive Load in the Flipped Classroom: Definition, Rationale and a Call for Research. Higher Education Research and Development,, 34(1), 1-14.

Buck Institute of Education. (n.d.). What is Project Based Learning (PBL)? Retrieved from BIE: http://www.bie.org/about/what_pbl

Hattie, J. (2005). What is the nature of evidence that makes a difference to learning? Retrieved March 4, 2017, from ACER Research: http://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=research_conference_2005

ITL Research. (2010). 21CLD Learning Activity Rubrics. Retrieved from ITL Research: https://education.microsoft.com/GetTrained/ITL-Research

Newman, D., Griffin, P., & Cole, M. (1989). The construction zone. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. (1983). The Instruction of Reading Comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 317-344.

Schlechty, P. (2011). Schlechty Centre on Engagement. Retrieved Novemeber 21, 2016, from Schlechty: http://www.schlechtycenter.org/system/tool_attachment/4046/original/sc_pdf_engagement.pdf?1272415798

Schuh, K. L., & Barab, S. A. (2008). Philosophical Perspectives. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. v. Merrienboer, & M. P. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology 3rd Edition (pp. 67-82). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.